Amid deadly anti-government protests, another Kenyan president is facing the consequences of confusing a parliamentary majority for popular legitimacy.

At the beginning of this year, William Ruto seemed on top of the world. A few months prior, he had come through a bruising contest and against the odds, as well as the machinations of his boss, he had been elected the country’s fifth president – William V as I like to call him. His main opponent in the race, Raila Odinga, had self-destructed not just in the run-up to the election when his 2018 handshake deal with Ruto’s former boss, Uhuru Kenyatta, had become a millstone around his neck, but also in the months afterwards when his challenge to the election results before the Supreme Court turned out to be little more than a farce.

In the months that followed, Ruto seemed to go from strength to strength. He is fashioning himself a reputation on the continent as something of a straight talker on the international stage – from complaining about the treatment of African heads of state at international dos to advocating for a new financial architecture to replace the Bretton Woods system. It has earned him some plaudits despite being a rather transparent attempt to resurrect his reputation after his and Kenyatta’s attempts in 2013 to bully the African Union into a mass walkout of the Rome Statute, which established the International Criminal Court, after the duo became the first sitting head of state and deputy to stand trial before the court for crimes against humanity.

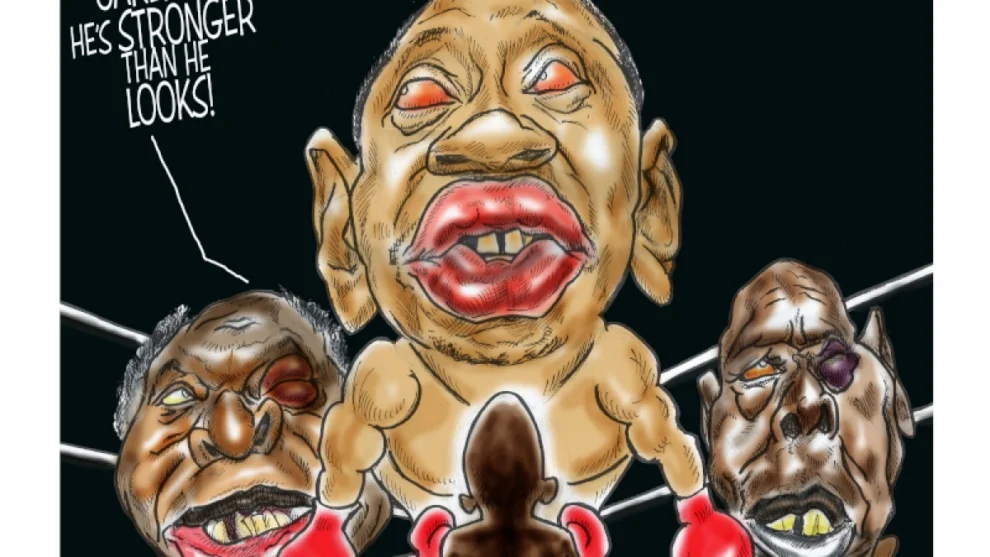

Meanwhile, his rival, Odinga, has seemed able to only flail at him from the margins. In the first weeks of Ruto’s administration, defections from Odinga’s coalition cemented Ruto’s majority in both houses of parliament, meaning the president’s legislative programme would suffer few impediments. Furthermore, Odinga’s programme of biweekly public protests and civil disobedience meant to delegitimise Ruto’s rule in the public imagination (as Odinga had successfully done to Kenyatta years before, eventually forcing him into a handshake) did not initially appear to attract a lot of public support, apart from in some areas of the capital and a couple of counties in the west of the country. The weekly scenes of Odinga’s motorcade playing hide-and-seek with police while trying and repeatedly failing to access Nairobi’s central business district were becoming something of an embarrassment as were the ever-changing lists of demands. Still, he did manage to push Ruto into the beginnings of a dialogue that collapsed almost as quickly as it got going.

However, all that seems to have changed.

The Ruto administration’s nearly 4.5 trillion shilling ($31.8b) budget and the taxes it plans to raise to finance it have proven to be something of a godsend for Odinga, supercharging public anger and backing for his protests. Suddenly, even in areas that had voted for Ruto, people are coming out to register their anger at parliament’s adoption of the Finance Act and the president’s signing it into law.

Opposed by seven out of 10 Kenyans, the law would double the VAT on fuel, whose knock-on effects would see prices rise across the board, introduce an unpopular housing levy and raise taxes on digital content producers and employees earning more than 500,000 shillings ($3,500) a month. In the past two weeks, at least 13 Kenyans have been killed in public demonstrations mainly centred around the rising cost of living.

It seems that Ruto is coming up against the limits of his power. His absolute majorities in both houses of parliament and his control of the executive may have somewhat obscured an obvious and fundamental weakness: that he does not enjoy much of a mandate. In last year’s election, he squeaked through with barely half of the vote (50.7 percent) in a poll boycotted by more than a third of the electorate. Of 22 million registered voters, only about 7 million voted for him. From such a weak position, he cannot really afford to pick a fight with Kenyans.

History has shown the folly of confusing a parliamentary majority for popular legitimacy, or worse, imagining it trumps popular legitimacy. Ruto’s predecessor also boasted of a super-majority – the so-called Tyranny of Numbers. He abused it by forcing through unpopular laws and, like Ruto today, was plagued by increasing revelations of corruption. With the sublimation of his popular legitimacy, his ability to govern wasted away. Despite winning a second term, only the handshake with Raila afforded him the room to rule. In fact, the humbling of would-be autocrats has been a running theme of Kenyan history over the past 30 years. And it is one Ruto would do well to pay attention to.

The ability to command the loyalty of a police force that can kill and brutalise your perceived enemies and a compliant, corrupt parliament that can give your oppression the veneer of law, in the end, will only delay an inevitable reckoning with the people. It took Kenyans a long time, many deaths and much maiming to win back their ability to impose their will on those who would rule over them. The various struggles to free themselves from the British and those who came after culminated in the adoption of the 2010 constitution, the first indigenously crafted and popularly endorsed system of government, and the first to recognise that sovereignty and power reside in and are drawn from the people.

Winning an election may give one access to public power, but that access has to be constantly negotiated during one’s term. And the people’s consent can be withdrawn at any time, with or without an intervening election. That is the essence of government by consent rather than by coercion. It is not about how many MPs support you. Rather it is about how many Kenyans do.

Source: Al Jazeera